Published by archerchick on 24 Mar 2010

The Perfect Treestand – By Bill Vanznis

The Pefect Treestand – By Bill Vanznis

Bowhunting World Annual 2006-2007

Your odds for success sour with this 15-item checklist!

The perfect stand should not stick out like the proverbial sore thumb. If it is visible from ground zero, it should look like part of the forest and nothing more.

There is no doubt about it.Hunting whitetails from an elevated platform is a killer technique! Position a treestand correctly, and you should easily avoid a buck’s sharp eyes, rotating ears and that uncanny sniffer of his long enough to take him with one well-aimed shot. This does not mean, however, that any stand site will work for you. Some setups are simply better than others. Here is how to turn the average treestand into a real killer.

1. SAFETY FIRST!

The perfect treestand must be safe to use treestands that have been left outdoors all

season long need to be inspected carefully for splits and cracks before you ever step on board again. Extreme weather, claimjumpers, saboteurs, animal rights idiots, and other assorted riffraff can and will raise havoc with any hunting property left unattended in the woods.

Even if you pull your stands at the end of each season, field-test each one before the opener. If you have any reservations-as to its safety or effectiveness, get rid of it and purchase a new one. Your life and well-being are worth a lot more than any whitetail.

What is the most dangerous treestand in the woods? The one that is handmade from leftover lumber! Rain, sun, and especially wind can weaken the wood and even help pull nails and screws from support beams causing it to collapse when you set your weight down. Never

trust them!

2. STRANGER

BEWARE!

The perfect treestand is one you erected, fair, square, and legal. Never hunt from a stranger’s treestand. Not only is it unethical, but it may be defective or not have been set up correctly, which in some cases could be an accident looking for a place to happen.

There are many problems associated with bowhunting out of a stranger’s treestand. You don’t know when the stand was last used, meaning the stand could already be overhunted. Nor do you know if whoever was on board spooked a buck into the next county, was as careful with human scent as you are, or is a meticulous in his approach and departure as you tend to be. Did he urinate off the stand? Did he gut-shoot a deer earlier and spend the morning traipsing about looking for it? If so, you are probably wasting your time. In short, the only thing you know about this is such a hot setup, why isn’t the owner or one of the friends on board?

3. UP-TO-DATE SURVEILLANCE

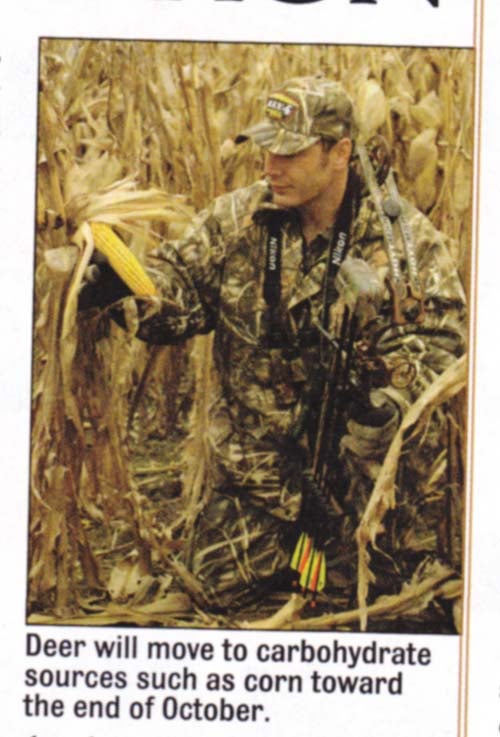

The perfect treestands is erected only after careful consideration of a host of factors, including food preferences, weather conditions, hunting pressure, stage of the rut, etc. Don’t set up a stand based on last year’s scouting information. Sure, you tagged a nice buck there last fall, but a lot could have happened in the interim. Crop rotation, a poor mast crop, new housing projects and logging operations can all have a negative impact on a deer’s daily routine and cause him to abandon last year’s hotspot.

4.KEEP YOUR SECRET HOTSPOT A SECRET!

The perfect treestand is one only you and a close friend know about. Do not brag about the bucks you are seeing on Old McDonald’s farm, and don’t give details about the stand’s exact whereabouts. Tell the boys at the archery shop you have a stand in the old apple orchard, and sooner or later one of those guys will be setting up nearby —legally or otherwise.

Even if you are tight lipped about your hunting turf, do not park your vehicle near your hunting grounds or an obvious trailhead. Instead leave your vehicle some distance away to help confuse trespassers and claim-jumpers as to the exact whereabouts of your treestand. Remember, loose lips sink ships!

5.TO TRIM OR

NOT TO TRIM

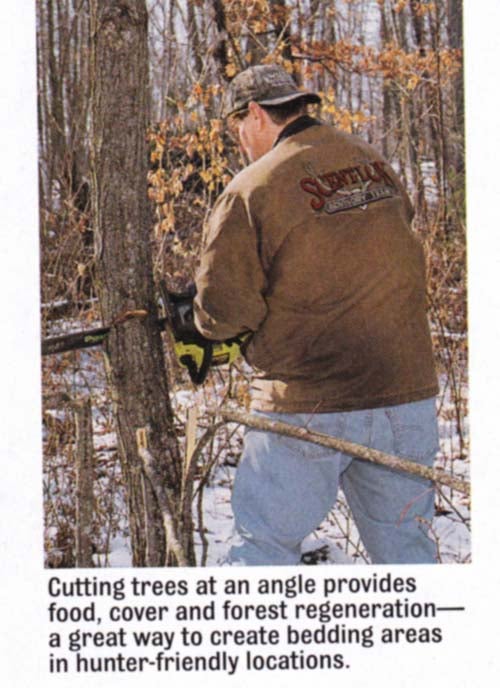

If you must trim branches around the stand, do so sparingly, and only enough to come to full draw without interference. Just remember that the branches that you cut away are the same branches that afford you cover.

The same goes for shooting lanes. Keep in mind that mature bucks do not like to stick their necks out. Wide, open shooting lanes spell d-a-n-g-e-r to an alert buck and are subsequently avoided. Besides, the brush you cut down and remove is often the very same cover that attracts local bucks!

In addition, nothing alerts an incoming buck, or another hunter for that matter, to the exact whereabouts of your setup better than several white “spears” sticking up from the ground. Use an old trapper’s trick, and smear dirt and leaves on the “stumps” of cut saplings to help hide them from prying eyes- Camouflage those shooting lanes!

6.APPROACH UNDETECTED

The perfect treestand approach the site and then climb on board without alerting any deer to your presence. You can start as soon as you park your vehicle by remaining quiet as you assemble your gear. Do not talk, slam doors, or wave flashlights about.

Check the wind and then choose a route that affords you the most privacy. You do not want your scent drifting into suspected bedding grounds or preferred feeding areas, nor do you want deer to see you crossing open fields or gas line rights-of-way either. Nor do you want to

cross any hot buck trails.

Even with all these safeguards in place, wear knee-high rubber boots and be careful what you touch or rub up against. The scent you leave behind can spook a deer long after you are in your stand.

Be sure to walk slowly and quietly, stopping often to listen. In some cases a cleared trail may be necessary. Deer can instinctively tell the difference between man and beast moving about. Humans walk with a telltale cadence and a destination in mind whereas a deer will travel in a stop-and-go manner.

Finally, get into your stand quickly but quietly. Once settled in. use a fawn bleat to calm down any nearby deer.

7. NO HIGHER THAN NECESSARY

The perfect treestand is positioned no higher than necessary. In some cases a

10-foot perch is more than high enough off the ground to be effective, whereas in other situations a stand 15 to 20 feet up is required. Keep in mind that the higher you go, the more acute the shot angle becomes on nearby deer.

The late season has its own set of problems. There is less cover, and those few bucks that somehow survived the fall fusillade are on high alert. You can overcome some of these obstacles by placing your treestand a few feet higher than usual and positioning it so that you take your shot sitting down after the buck passes you by. A quartering-away shot is the best angle for a nervous buck.

8. COMFORT ZONE

You should be able to stay aloft all morning or all afternoon if necessary in a perfect stand. Start by choosing a stand design that allows you sit still without fidgeting. A seat that is too high, too low, or too small can cramp your leg muscles forcing you to stand and stretch. So can a stand that is not positioned correctly. If the stand is tilted, it will throw your weight off balance as will a knot in the trunk pressing against your back. Even facing a rising or setting sun can raise havoc on your ability to remain motionless during prime time.

9. SCENT-FREE

The perfect stand is clean and free of human odors. This means you are careful in your approach and exit routines, and you do not wander around the area looking for more deer sign or pacing off shooting distances. Use a rangefinder and write down the distance to various objects for future reference. Tape them to the inside of your riser if need be.

Some hunters go so far as to spray scent eliminators on anything they touch

or rub up against, including tree steps, pull-up ropes and the tree itself. You can never be too careful in this regard.

10. PLAYING THE WIND

The perfect stand takes advantage of prevailing winds, but you should have a second or even third stand already in position to take advantage of major changes in wind direction brought about by storms and other varying weather conditions.

You must not be tempted to sit in your favorite treestand if the wind is blowing your scent in the direction you expect a buck to come from. Once a mature buck knows you are lurking nearby, he will undoubtedly avoid the area for several days—or the rest of the season.

11. OUT OF SIGHT

Position your treestand in a clump of trees whenever possible, as opposed to a single tree with no branches. Not only will it less likely be picked off by a passing buck, it will also less likely be stolen by a passing thief. If you are unsure if you are silhouetted or not, view the stand from a deer’s perspective, and then make adjustments as necessary.

12. SHOOT SITTING DOWN

The perfect stand allows you to make the perfect shot by coming to full draw undetected. Sitting down is the obvious choice because it requires only a minimum of movement to complete the act. If you must stand to make the shot, then position your stand so you can use the trunk of the tree as a shield.

13. OVERWORKED

The perfect stand is not hunted on a daily basis. In fact, it is hunted only on the rarest of occasions when all conditions are, well, ideal. And ideally, you would only hunt from that stand once, taking one well-aimed shot at a buck before you climb down from your first time on board.

Otherwise, any more than three times a week would be excessive. Remember, whitetails can pattern you rather quickly and will avoid your stand site as soon as they realize you have been snooping around on a regular basis.

The only exception is during the peak of the rut when bucks from near and far are pursuing does 24/7. Those stands that are set up along natural funnels can be bowhunted almost daily now where any buck you do see will likely walk out of your life forever if you don’t put him on the ground first.

14. PORTABLE OR PERMANENT?

Is the perfect treestand a portable or a permanent setup? Permanent stands have a built-in problem. As soon as a buck picks you off, he will avoid that setup, giving it a wide berth whenever he passes nearby, making the life span of that stand rather short.

Another problem with permanent stands is that they are difficult to fine-tune. You may be in the right church, so to speak, but in the wrong pew, making it impossible to move the 5 or 10 yards needed to get a killer shot.

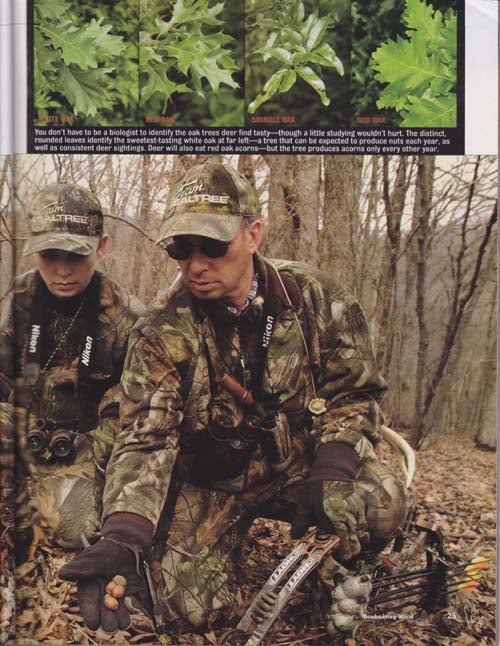

A third problem with permanent treestands is that they do not allow you to move about as the season unfolds. For example, you want to key in on food sources in the early season, such as alfalfa, corn, beans, peas and buckwheat, but what do you do if things go sour? A good windstorm, for example, can shake the season’s first acorns loose, luring local bucks away from agricultural crops and into the swamp bottoms and steep hardwood ridges to feed on the fallen mast. How are you going to take advantage of this situation if you are relying on permanent stands built during the off season?

15. EXIT STRATEGIES

The manner in which you exit your stand is as important as your approach to your stand. When you step off the stand, push the main platform up against the trunk of the tree to help reduce its silhouette. Weaving a few dead branches into the stand’s frame will also help. You want your stand to remain hidden from deer and human eyes.

Next, get out of the stand quickly and quietly, avoiding all metal clanging. In case an unscrupulous hunter does find your stand, undo the lower set(s) of steps and hide them nearby. He may have found your secret stand site, but it is unlikely he will be able to hunt from it—at least on the day he finds it!

Now choose an exit route that will help you avoid contact with any deer. Keep in mind that you may be able to get to your stand quietly in broad daylight, but what about after dark? Can you sneak out without making a racket or disturbing nearby deer? After a morning hunt, you can cross most openings with impunity, but in the evening you would need to avoid meadows and other feeding areas even if it means taking the long way around.

A common mistake bowhunters make in the evening is walking out quickly and in a forthright manner. As with your approach, you must “bob and weave,” avoiding known trails and probable concentrations of deer. Sneak out, and when you get to your vehicle don’t talk, turn on the radio, or bang gear around. Deer will Patten your exit strategy as quickly as your approach.

As you can see, there are a lot of things to think about before you install a treestand. Think about each of these components carefully, and your chances of scoring will soar.

Archived by

ARCHERYTALK.COM

all rights reserved

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices