Published by archerchick on 09 Dec 2011

The 10% Club – By Tim Burres

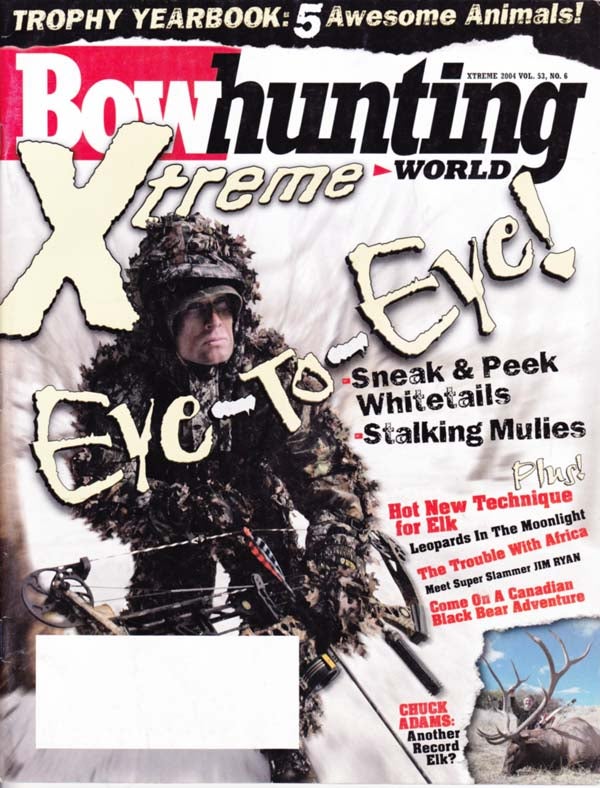

Bowhunting World Xtreme 2004

The 10% Club – By Tim Burres

Only 10% of the bowhunters consistently bring home the trophies. Here’s what you can do to join this elite club.

If you don’t belong, you won’t find a bouncer to

turn you away at the door of the 10% Club. There’s no

specific meeting place. But, you will know when

you’ve met one of the card carrying members. He will

be the guy with the trophy room full of big deer. To

join the club, you don’t have to be famous and you

d0n’t have be the founder of an oil empire. You don’t

even have to be a particularly winsome fellow-

which makes membership a possibility for everyone.

You pay your membership dues over a period of

years with countless weeks spent in treestands.

Members of the 10% Club may seem like geniuses when you

dissect some of their hunting strategies, but Mensa is

one club very few will ever make it into. They may not

scare Einstein in an IQ contest, but what these members

do have are open minds that permit them to view

every hunting situation as if it were a blank slate.

These 10% Club members enter every hunt without preconceived

notions of what is “supposed to happen” or some idea that

they must do things “the right way.” And they are meticulous

to the 9th degree in everything they do involving deer

hunting. Here’s what you can learn from the Board of Directors

at the 10% Club.

THINKING OUTSIDE

THE BOX

I ran across a perfect example of why some hunters are consistently successful while others are not. This example shows the

power of thinking outside the box and being aggressive when the situation calls for it.

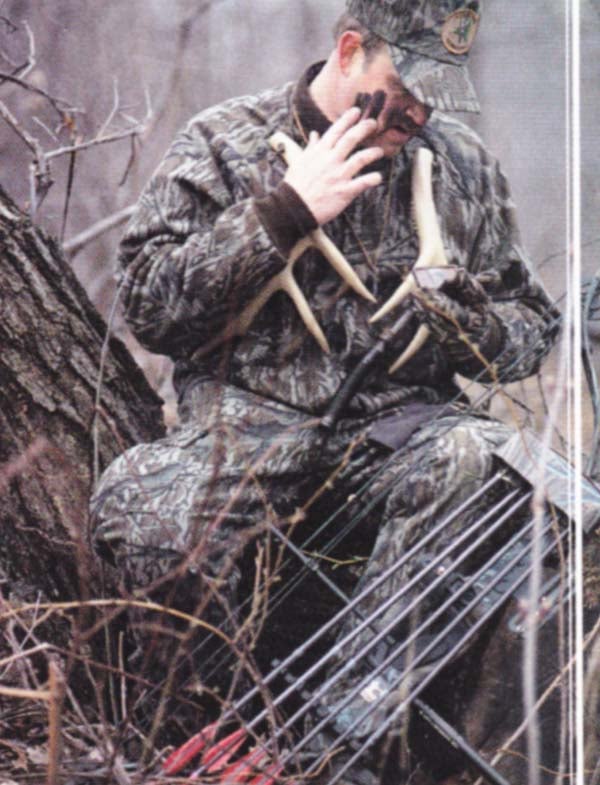

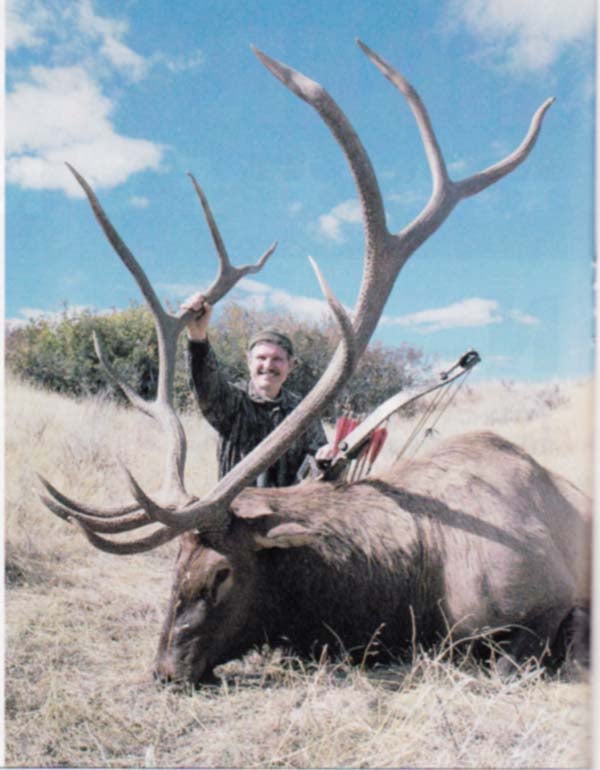

Stan Potts has been a regular fixture around central Illinois’

Clinton Lake Wildlife Management Area for at least two decades.

Some years he has hunted on the limited draw public lands and other

years he has hunted private land in general area. During the early

‘90s a great 6×6 buck lived on the public management area. All the hunters knew about him and everyone wanted to get a crack at him

One day Stan was hunting a stand in a fence line along the edge of a picked cornfield when he saw the buck bedded with a doe in a thin patch of giant foxtail grass in the middle of the field. It was the peak of

the rut and Stan knew the buck was holed up out there with the doe. In fact, Stan even saw the buck breed the doe once during the morning session.

Rather than wait and hope the buck would eventually get up and come past,

Stan decided the best strategy was to take the hunt to the deer. There is never a better time to make your play for a big buck than when you know where he’s at.

They are so tough to even get a look at that when one is right there in front of you it’s important that you do everything possible to get the shot right then. Stan knows that from having hunted big bucks for all his adult life.

After a few quick plans were made Stan climbed down from the tree and

carefully began stalking the buck. Unbeknownst to him, a bowhunter from Oklahoma was watching the show from a stand on the other side of the field.

“Later the guy told me that when he saw me start the stalk he said to himself ‘Oh no, whats this moron doing?”’ said Potts. “The situation was right or I never would have tried the stalk. The wind was blowing hard and it was misting rain. The cornstalks were soaked and the ground

was soft so there was no way the deer would hear me. Also, the wind was perfectly in my favor so I could sneak in on the deer from behind.

If they had stood up at any time they could have seen me even if I was lying down. I moved along one row at a time. I’d rise up on my elbow, make sure they weren’t looking and then roll gently onto my back in the next corn row.

“The suspense was killing me as each row brought me another yard closer. Finally, I counted only 50 rows between the deer and myself but I didn’t have an opening to his chest. There was no way I could wait until they stood up or they’d see me instantly. I had to make the shot while he was still bedded. There was an opening in the grass a short ways to the side so I eased into position. From there I was only 25 yards from the buck.

I turned the bow sideways and drew it as I rose up slowly onto one

knee. He never knew I there. The shot was perfect and when they blew out I could see the nock of the arrow sticking out of his chest. I knew he wasn’t going far. The buck only ran about 50 yards before making a

button hook and going down.

“The excitement had been so intense that I could hard stand it When he went down I was in shock still standing there staring at the buck when the guy from Oklahoma runs right up from behind and yells at me he about scared me out of my skin. Then we celebrated together. He was a great guy and was just as excited as if he’d killed the buck himself. He told me how he had watched the whole stalk from the treeline. After things calmed down he told me that he had been watching the buck for two days. His ear-to-ear grin immediately disappeared when I casually asked him why he hadn’t tried the stalk himself. His eyes fell to the ground and he shook his head and said in a very soft voice ” I don’t know.”

Stan’s buck was a local legend with a massive rack having a gross score well over 170 inches and a net that came in just under 170. He got the buck because he was able to think creatively and adapt to the situation at hand. He didn’t get bogged down in what he was suppose to do, but rather focused on what he knew about mature buck behavior (they are very hard to see more than once) and what might work. Taking advantage of the situation permitted an effective stalk, he did something most bowhunters would be afraid to even try.

The ability to think creatively is one of the traits that set the members of the 10% Club apart from all the other deer hunters. Textbook strategies will sometimes work, but mature bucks are individuals. To tag them consistently you have to treat each one as if he were the only deer

on earth. It is unwise to assume anything about a particular buck beyond the fact that he is sure to be wary.

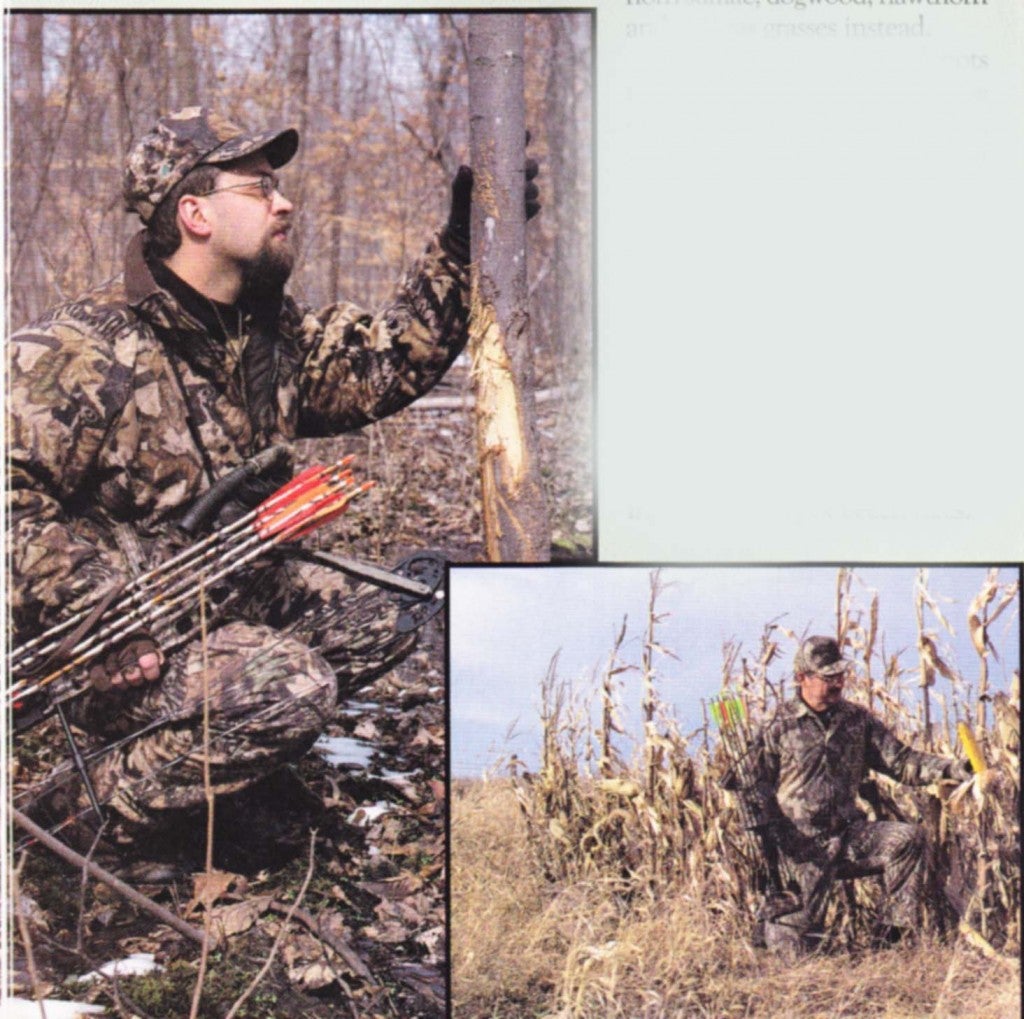

From bits and pieces of sign and sporadic sightings, you may be able to piece together enough information to learn the buck’s particular personality and within that you may be able to find some type of

behavior that makes him slightly vulnerable.

You won’t find much to work with, because these deer are not very visible and they are the most cautious creatures on earth.

Once you get to know a little bit about the buck you can determine such things as whether or not he’s aggressive (if he is, rattling might work). You might figure out where he most often beds and feeds you

might be able to find an ambush between these points) and whether or not he is an active participant in the rut (if he isn’t your only real hope is catching him at his bed or late in the season at a food source.

If you enter the hunt with a cast-in-stone idea of what mature bucks are

“supposed to do,” you will have a very hard time adapting to what the buck you are hunting actually is doing. The ability to keep an open mind in your approach to hunting specific bucks is one key that

opens the door to the 10% Club.

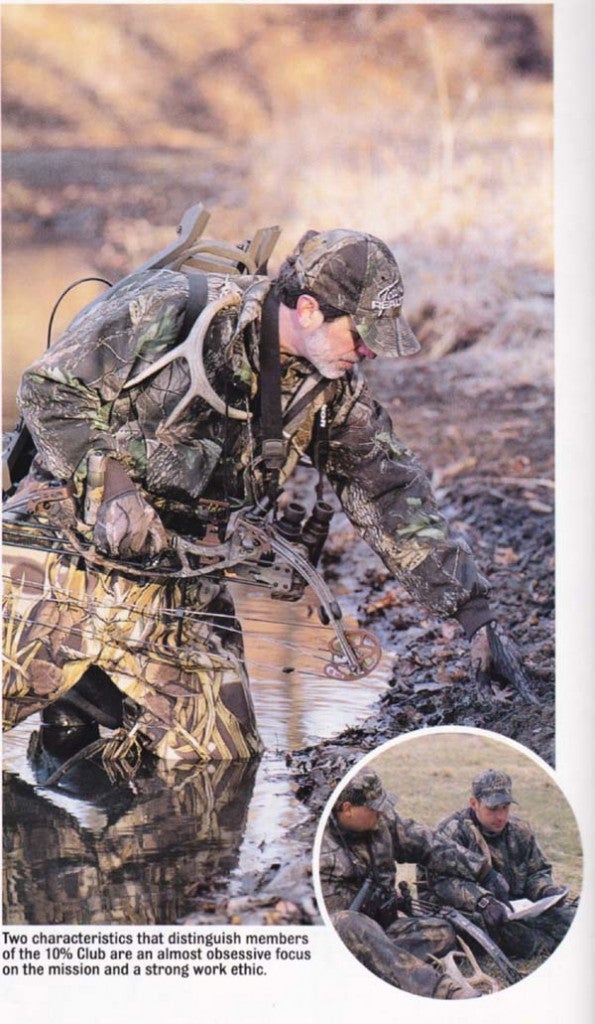

ATTENTION TO DETAILS

The second trait that club members share is an overpowering belief in the notion that if it can go wrong it will. Therefore, they are detail oriented people that aren’t willing to let even one small aspect of the

hunt that can be controlled slip through their grasp. For this reason they are extremely thorough in everything from shooting practice and equipment maintenance to scouting and stand placement.

Here are some of the details that 10% Club members wake up in the middle of the night fretting about that other deer hunters barely consider.

Entry and exit is the key: I remember a stand one of my buddies offered me while I was hunting with him a few years ago.

Even though we sat on the county road looking at the stand across a picked grain field, it still took him five minutes for him

to explain what I had to do to get to it without being detected. “Go behind that house and around the pig lot, get into the creek, grab the roots under the high bank and climb up, etc.” I knew instantly that

this was going to be a good stand. Anyone who understands the importance of the exit and entry routes this well is bound to

have great stand locations.

I can always tell a good hunter when listening to his explanation of a stand because he is obsessed with the perfect entry and

exit routes. Experienced hunters know that these routes are even more important than the sign the stand overlooks.

Average deer hunters can all tell you where to find buck sign. Members of the 10% Club have mental maps too, but they aren’t marked with buck sign and deer trails; they are marked with all the undetectable entry and exit routes that dissect their hunting areas.

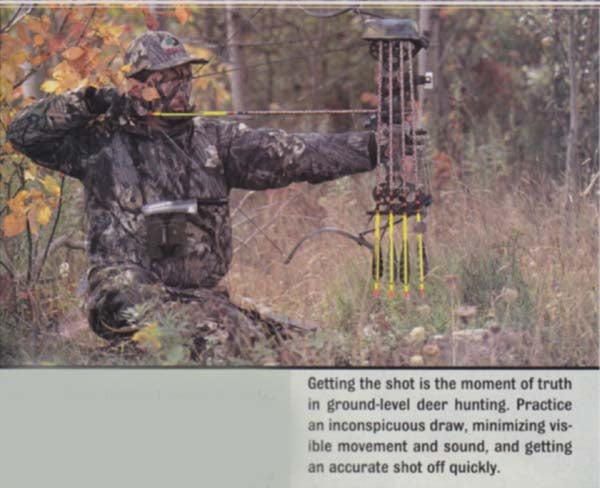

Shooting lanes; Once you start to realize how hard it is get a giant buck within range of your stand you’ll do everything possible to capitalize on these infrequent encounters. In other words, you need to be

able to get a good shot at him. Members of the 1O% Club know all too well the importance of having shooting lanes in every direction. By this, I’m not talking about dropping napalm on the acre of cover surrounding your stand; all you need is a window — some kind of gap — that allows you to get a shot at anything that passes your stand in any direction and at any distance within your maximum range.

Before you relax after climbing into your stand, take the time for this exercise. If you will do it every day you will be rewarded during the moment of truth. Imagine a buck approaching from every possible direction. How will you handle each possibility and where will you shoot?

If you don’t have a good answer it’s time to get the saw out and create an answer.

Intelligent diligence; I recently returned from Alberta where l was hunting with an outfitter who is a new bowhunter. He is a great gun hunter but not a great bowhunter. I was pretty much on my own.

After we discussed bowhunting strategy for a week—and applied some of it in the form of stand sites-Ron made a very insightful comment to me. He said, “Successful bowhunting can be summed up as intelligent diligence.”

Ron had quickly figured out that you have to combine equal parts of

hard hunting with smart hunting. It was clear to me right then that Ron was on the fast track to getting his membership card.

OTHER REQUIREMENTS

FOR CLUB MEMBERSHIP

Keen instinct; Some guys will never meet the 10% Club’s minimum requirements for membership for “hunter’s instinct”. Quite frankly, they aren’t interested enough in the behavior patterns of mature bucks to learn everything they possibly can about them. Sure, they want to shoot one, but the animal doesn’t fascinate them to the extent necessary to stimulate their need to know more.

Highly successful buck hunters are more than just students of the latest biological research; they are on the cutting edge of research. They are always coming up with theories to explain some kind of behavior they see and then focus on trying to prove it or disprove it. The final goal, of course, is to find weaknesses they can exploit. I respect everything that

comes out of the mouths of the top biologists, but I put just as much stock in the words of proven buck hunters.

Making the shot: Not only are the members of the 10% Club hard and smart

hunters, they are good at converting opportunities into venison. Even the best hunters may only get a very limited number of close encounters during a season —sometimes none- so they take each one of them very seriously. They condition their minds so that they are prepared to convert on every decent chance that comes along. This is not a skill that

people are born with. It is something that is built through-you guessed it—attention to detail and lots of practice.

When a big buck causes your throat to tighten, the only thing that will pull you through is the many hours of disciplined practice that came before. Great habits during practice translate into great performance when the chips are down. If you are serious about getting into the Club,

realize that your ability to shoot well— without having to think about it- will someday be the only thing that stands between you and a wall full of trophies.

CONCLUSION

Membership in the 10% Club requires that you go beyond the simple preparations and actually do all the things that you know you should do. Most guys that have read magazines about deer hunting know what to do, they just don’t do it. Rising to the next level takes dedication, effort and time. But, if you love deer hunting, the quest will become its own reward.

Archived By

www.Archerytalk.com

All Rights Reserved

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices