Published by archerchick on 21 Mar 2010 at 10:03 pm

Quick Kills On Big Game – By Russell Tinsley

Quick Kills On Big Game – by Russell Tinsley

November 1971 ARCHERY WORLD

BOWHUNTING IS a sport of inches. Sometimes just a couple inches will be the difference between a hit or miss, and even a fraction of an inch might determine a quick kill or just a

crippled animal. Yet shooting a bow and-arrow is such a tough procedure that error usually is measured in inches rather than fractions thereof. So the bowhunter “hedges” on his return by reducing this mistake factor to its lowest possible denominator.

This is accomplished in several ways. Having the proper equipment which is prepared correctly is perhaps the foremost consideration. Being a skilled hunter and getting the very best shot with the least margin of error is another. And of course knowing where to place the arrow for optimum results.

A fast-propelled arrow striking an animal’s vital organs should accomplish two rudimentary assignments: create intense hemorrhaging or bring quick and humane death, and encourage sufficient external bleeding to have an easily followed blood trail.

Simple mathematics tells us that a heavy object traveling at a rapid rate of speed will create the most damage upon impact, and this is true even of an arrow which kills by hemorrhage rather than shock. The more Penetration an arrow gets, the better are the chances of getting massive damage to internal organs. And the farther a sharp broadhead- tunnels through the animal’s body cavity, the more opportunity it has to come in contact with organs and disrupt their functioning.

Bob Lee, veteran bowhunter and president of Wing Archery Company, says the draw-weight of a hunting bow “should be as heavy as a person can adequately handle-and I mean handle and not merely shoot.”

The basic theory behind this, of course, is that the heavier bow will cast heavier arrows at a faster velocity, and this results in better penetration.

“But be sure the bow and arrows are matched,” Lee adds. “This is a common mistake among many bowhunters, having mismatched tackle, and a person can’t get the needed accuracy with such equipment.”

By proper conditioning and training of the muscles, the hunter can learn to handle – there’s that key word again-a bow of heavier draw than he is now using.

But even driving an arrow completely through an animal is of questionable value unless the broadhead severs organs to induce bleeding. The bowhunter can greatly improve his odds for success simply by having his broadheads honed sharp. A dull head tends to roll flesh and organs aside while the razor like head cuts cleanly.

As a person practices with his equipment he becomes aware of his limitations and capabilities. If you, for example, find that at ranges beyond 25 yards your aim is erratic and arrows scatter, then work for shots at less than this distance. Whether you shoot instinctively or use a sight isn’t important; what is imperative is that you can put the arrow where you want to.

Now we come to that moment of truth when you are drawing on a big-game animal. Where should you aim to get the quickest kill?

If the critter had a bull’s-eye painted on it, this would be a simple matter. But the hunter usually has just a brief time to size up the situation and determine where his point of aim should be. No two shots are exactly alike.

Maybe the animal is standing broadside, quartering away or facing you. The arrow kills a critter by disrupting either of its most vital life-sustaining functions: the nervous system or the movement of blood. The most surefire is to stop all or part of its nervous system. One deer I killed was trotting by my tree stand and I led the animal too much and instead of hitting behind the shoulder, where I

intended it to go, the arrow struck the buck’s neck and completely severed the spinal cord. The deer fell there.

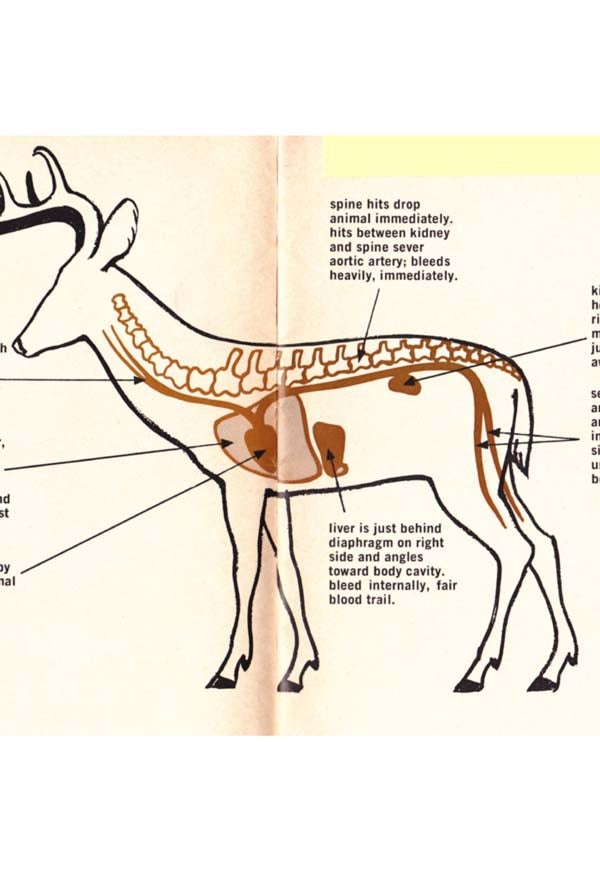

But trying for a spine hit is too much of a gamble unless maybe you are in a tree stand and the animal is walking directly beneath you. Even if you are off just an inch or so to either side, the broadhead still will bury into the body and find blood-carrying vessels.

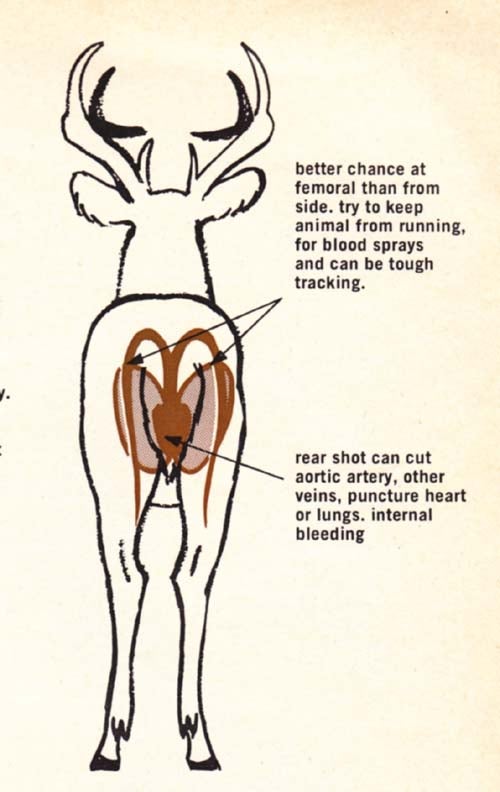

An animal’s body is a network of arteries and veins which all originate at the heart. Hit the heart or any major artery and you will get profuse bleeding; smaller vessels will give progressively less. I once shot at a buck which ‘jumped the string”. The arrow caught him in the ham, striking the

femoral artery. The resulting blood trail appeared as if it had been poured from a bucket. The deer traveled less than 35 yards before going down.

The ideal spot to induce the most bleeding, it would seem, would be the heart. It would. But the heart of any animal lies very low in the throat between the front legs when the animal is viewed from the side. Here the forelegs, brisket bone and muscle give the heart quite a bit of protection.

If the arrow is forward too much, just an inch or so, it likely will strike the foreleg and perhaps just ricochet. A couple inches low and the projectile will pass beneath the animal a miss. Too far back and it is in the body cavity where it must hit an artery or vein leading to and from the heart to get the desired results. About the only margin for error is above the heart, where there is a cluster of organs,

All big-game animals are basically the same. You’ll find the same vital organs in the same places. But the overall picture is different. A white-tailed deer, for instance, has long legs, while the javelina is squatty, built close to the ground. An elk is a much larger animal with tougher skin and bones, and although its heart is correspondingly larger, it is much better protected against even I sharp arrow. The archer shooting from above-a tree stand Perhaps- stands a much better chance of angling an arrow into the heart region than does the hunter aiming from the ground, on the same level as his target.

To reach this area some bowhunters refer the flat two-bladed broadhead, reasoning that with the less resistance it will knife completely through the animal, severing everything in its path.

Bill Clemets, perhaps Arkansas most successful bowhunters, is a great believer in this type head. Me, I Prefer the multi-blade head, either three or four cutting edges, preferably four.

This type of head leaves a jagged hole which really pours blood. Also, should the head remain buried inside the animal, it will jiggle back and forth, continuing to cut, as the critter runs. But neither type is of much value unless it is sharp.

The bowhunter’s best shot, I’m convinced, is in the so-called- high lung area, just behind the shoulder. A hit here might not give as much blood as a heart shot, but it will be sufficient and in this area there is a bit more leeway for human error. lf your shot sails slightly high, you are apt to hit the spinal column; should it be low, you’ll be probing the heart and large artery region. The arrow even can be too far back by an inch or two and you will have a pretty solid hit. But let too far forward and the shoulder bone is in the way. If this bone is hit just right the arrow might penetrate; but usually it simply slides to the side or bounces back. I hit a mule deer in the shoulder while on a hunt in Colorado and the arrow bounced back almost to my feet. The broadhead tip was curled back. I doubt if the arrow created enough damage to even give

the buck a sore shoulder.

As the bowhunter becomes more experienced he will learn to aim to compensate for his own personal tendencies. With me, shots less than 25 yards tend to rise, while on out there

the arrow more likely will drop. So if an animal is close, I am low on the body. Should the arrow be on target I’m in the heart region, and even should it rise slightly I’ve got a fatal hit. On longer shots just the reverse is true: I am high, for the lungs, and even if the arrow does drop it will

connect with vital organs.

Most bowhunters think of the classic broadside as the ideal position for a shot. Since one-dimensional drawings are usually sketched this way, the hunter has a vivid mental picture of where all the animal’s organs are placed. This position comes closest to simulating target shooting. But if the animal senses something wrong and moves before the arrow arrives, then the projectile likely will hit the critter’s midsection. A high shot will pass through the body without causing any extensive damage; a low shot will find the gut region, and that is one you want

to avoid. While this might indeed be a fatal hit, there usually isn’t much external bleeding, making the animal difficult to trail, and a gut-shot creature is apt to travel for long distances before going down.

Much better than the broadside is the quartering shot. The rear quartering shot is preferred. Although the silhouette is not as large, more of what you see is vulnerable tissue. There is

less chance of a bone deflecting the arrow, and it furrows more lengthwise through the body. Common sense tells us that the farther an arrow moves through an animal, the better are its

chances of hitting vital organs. Should the arrow pass through the chest cavity there is a possibility that it might come in contact with all three vital organs – heart, liver and lungs.

From the rear, blind-side, of the animal like this, the hunter stands to put his arrow into a vital area without being detected. The head-on and front quartering shots are less desirable, one reason being that the alert animal is more apt to detect danger, and from the front body bones are a

greater obstacle.

But if you do get a head-on shot, aim for the so-called “sticking spot” just below the neck. Place an arrow solidly here and you have a dead animal. The broadhead carves directly into the body between the forelegs.

A temptation is to aim for the head. But most big-game animals have small and well-protected brains. You are more likely to get just a glancing lick than you are a kill. For the front-quartering shot, aim just behind the shoulder. While the heart, liver and lungs are fairly well protected from this angle, the network of arteries and veins just beyond are vulnerable. If the arrow angles across

the animal, you probably will find a blood-carrying vessel. I once watched my hunting buddy Winston Burnham shoot a javelina that was trotting down a trail toward his stand, and while the

arrow hit a mite too far back, it traveled almost the entire length of the body, exiting just forward of a ham.

An autopsy revealed that the broadhead hit a rib, forcing the arrow upwards where it traveled just beneath the spine, severing several arteries and veins. The javelina wheeled around wildly once or twice, then made just two or three jumps before falling.

Now assuming you understand and know the vital areas and how to hit them and you’ve made what you consider a solid hit, then what do you do?

The consensus of most experienced bowhunters is to wait at least an hour if you think your . arrow hit the liver area or the rear half of the animal. Unless spooked, the critter usually will

journey just a short way before lying down. It becomes weak rather quickly and probably won’t have the strength to ever regain its feet.

But if the arrow hits the chest cavity and results in plenty of blood, it doesn’t make any difference whether you wait or not. The animal – be it an immense specimen like the elk, a

medium-sized one such as a mountain goat, or even the diminutive javelina -won’t travel far away. If you merely sever a large artery-you can tell if the hit results in an unbelievable amount of bleeding – then you will have no problem trailing and finding the critter.

Should the hit be in a non-vital section of the fore body, you probably will be wise to keep pushing the animal. An embedded broadhead will continue to cut and damage organs.

Even if the arrow completely passed through, don’t give the animal the opportunity to lie down and allow the broken blood vessels to clot. No matter where you hit an animal, don’t give up on it until you are absolutely satisfied that the carcass or some telltale sign can’t be found.

Sometimes the animal might flee along way before commencing to bleed. It isn’t unusual for one to go down without leaving a blood trail of more than just a few scattered drops. Watch which direction the critter runs and pinpoint your search in that direction. Try to find tracks, if nothing else, and search the trail meticulously for any sign which might reveal where the animal was hit. Perhaps you will soon locate the discarded arrow, broken or pulled out, or a pool of blood when

the animal stopped briefly. It is amazing the number of animals that can be found which at first were thought to be lost.

There is no satisfaction quite like that of staying doggedly on a trail and ultimately realizing success. That’s the mark of a true and dedicated bowhunter.

Archived by

ARCHERYTALK.COM

all rights reserved

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices