Published by archerchick on 17 Feb 2011

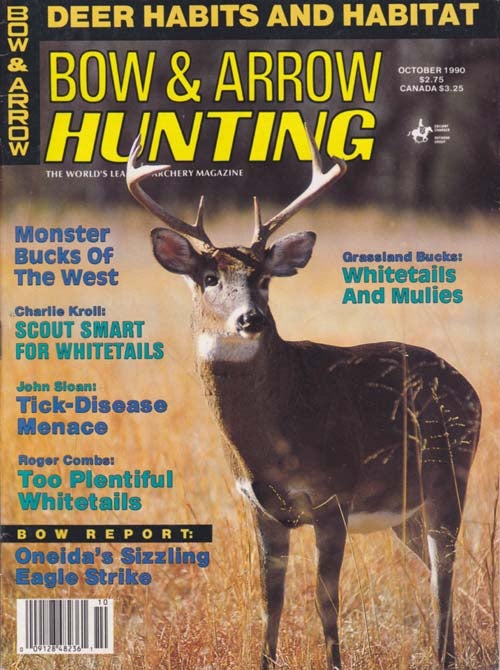

Grassland Bucks~ By Ralph Quinn

Bow And Arrow Hunting

October 1990

GRASSLAND BUCKS ~By Ralph Quinn

WHEN bowhunters think of wild, game-filled territory, they

often think of the rugged Rocky Mountains. Yet, some of the our most pristine

and productive big—game country lies in a corridor of grasslands occupying

landscapes west of the Mississippi river.

It begins in eastern Minnesota, with outliers in Iowa and Missouri, the

grasslands stretch westward to the Rockies, plunging south from Alberta to

the Texas Panhandle. Within this geographic zone, there’s a variety of

habitats from high desert plateaus, sagebrush flats to lowland savannas with

marvelously rich soils. Unlike the mountains, grasslands are subtle in nature —

as are the animals that inhabit these unique biomes.

Life here is compressed into a shallow zone between the soil and the tallest

trees. This is a land of arroyos and coulees, cottonwoods, yucca, bunch

grass, prickly pear, wild plum and wild roses. At first glance, this stark, wind-

swept country seems devoid of wildlife; but on second glance, the grasslands

come alive. In the vegetative understory sharptail grouse, rabbit, fox, coyote and

badger scamper about. On nearby prairies and sagebrush flats, sleek prong-

horns roam freely. And somewhere in the rolling flower—specked hills and

cedar edges, if we glass long enough, are deer — both whitetails and mulies.

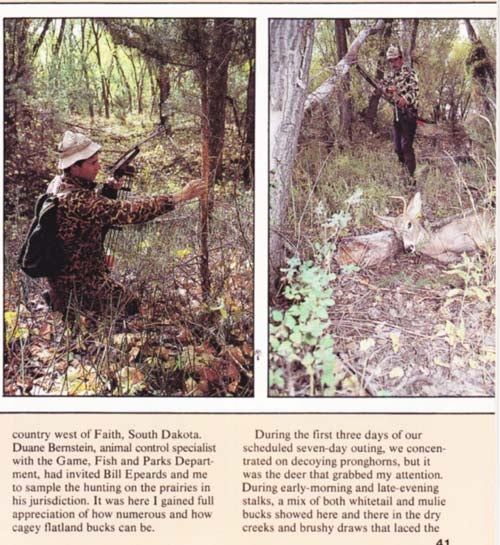

My first encounter with grassland bucks came in 1985 during an antelope

hunt in the cattle, sheep and coyote country west of Faith, South Dakota.

Duane Bemstein, animal control specialist with the Game, Fish and Parks

Department, had invited Bill Epeards and me to sample the hunting on the prairies in

his jurisdiction. It was here I gained full appreciation of how numerous and how

cagey flatland bucks can be.

During the first three days of our scheduled seven—day outing, we concentrated on decoying

pronghorns, but it was the deer that grabbed my attention. During early—morning and late-evening

stalks, a mix of both whitetail and mulie bucks showed here and there in the dry

creeks and brushy draws that laced the country together. Amazed to find deer in

such open country, I ask our host what we were seeing.

“These whitetail bucks are habitat specific, preferring to mix open spaces

in August and September with the seclusion of cedars, breaks and bottoms in

October and November,” Bernstein explained. “I guess they want privacy

early on and nighttime forays into the grasslands provide it. With browse,

water and bedding cover readily available, the deer stick in this kind of country,

especially the whitetails. They`re highly adaptable and to hunt them successfully

with bow and arrow you have to do the same.” This is an important

lesson for hunters wishing to pursue grassland bucks for the first time.

The following season — 1986 — I traveled is the mixed prairie and sage

country of Wyoming`s Area 24 near Ranchester and bowhunted the Tongue

Creek region adjacent to the Montana border. Leo Dube. of Trophy Connections.

runs an elk and mule deer camp out of Sheridan. but it was the whitetails

that really interested me.

“We have more than a few good bucks roaming the river and creek bottoms near

here.” said Dube. “I’ve collected my share of P&Y specimens.

Why don’t you pack your tree stand and climbers and sample the hunting?”

To make a long tale short, I saw some excellent whitetails along the Tongue

River and Clear Creek around Arvada, but settled for a 3×3 on the final day of

my hunt.

Twenty-five or thirty years ago, this section of Wyoming would have been been

considered mule deer country and still is, yet in the last decade, whitetails have

made a strong showing in the bottomlands. From all indications, they’re there to stay.

According to Roger Wilson, wildlife biologist with Wyoming Fish and

Game, based in the Tongue office, whitetails make up twenty—live percent

of the kill in Area 24, and…”the population is high compared to the previous

eight years.”

Neighboring Montana is experiencing a similar pattern, with whitetails making

up a larger segment of the total herd, with many areas expanding at record

rates.

Other grassland states -— Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, eastern Colorado — are

showing similar mini booms in whitetail numbers, in spite of near record kills.

“What we have,” comments Kari Menzel, big—game specialist with Nebraska

Game and Fish, “‘is an edge animal that’s adapatable and gets along well in

the eastern prairies. Where we have large blocks of agriculture going on,

he`s at his best, thriving on a number of grain crops, from milo to wheat. Not so

with the mule deer. The more we disturb his nomadic nature, the more we limit

his reproductive potential.”

Another factor directly related to increased whitetail populations is the

food base adjacent to the grasslands. In place of seasonal browse and grasses,

deer have a virtual cornucopia of energy·rich foods to draw on, even during the

roughest winter. As the arms of center~pivot irrigation sweep across the

plains states, the whitetail isn’t far behind, vacuuming surplus grains such

as milo, wheat, beans and corn, plus lush forage like alfalfa, spelts and cane.

A healthy herd translates into increased reproductive potential. The net results

are some pretty heavy—bodied and horned bucks that now roam the

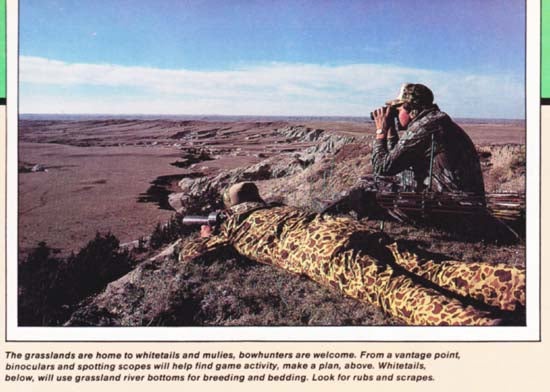

grasslands. If you’re a first—timer at pursuing grassland bucks, I advise, particularly in

new, unfamiliar territory, setting up a 20X spotting scope or tripod-mounted

binocular — 10X — on a high point, then pick the countryside apart. I like to call

this style of bowhunting “bucks by the seat of your pants,” and that’s a pretty

accurate description of the tactic. Watch for activity early and late, keeping in

mind that grassland whitetails prefer to bed low along creek bottoms and feed

high, returning shortly before daybreak.

Mark those points where bucks/deer appear and disappear.

The ideal strategy is to arrive two or three days ahead of your hunt and pinpoint

crossings. traveling, feed plots, etcetera. lf you’re after any deer, set a A

tree stand a minimum of fifteen feet on or near a creek—crossing or grain crop

area and hate at it. But if you are looking for something special, take your

search one step further.

In many grasslands states, both mule deer and whitetail habitats overlap, so

you may have to go with the flow. On private ranch Operations, where access

and harvest are tightly controlled, mulies survive quite nicely, as do whitetails,

in the open prairies and grasslands. Being a habitat generalist, he is comfortable

with foothills, prairie and river bottoms, but prefers open country.

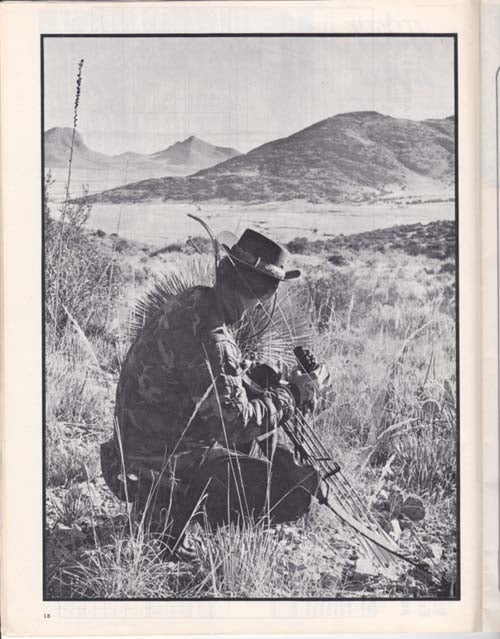

Again, if mulies dominate, set up your glassing operation on a high point and

look for deer movement from 9 or 10 a.m., then concentrate on stationary

objects from 11 to 2 p.m. Mulies usually bed then and, although not entirely

motionless, they’re tough to see. From 3 p.m. on, watch for movement again.

Mule deer like to bed high for visibility, then feed down in evening. Grassland

bucks, whitetails and mulies, have excellent long-range vision, similar to

antelope. So once the game is in sight, it`s still hunting with the emphasis on

“slow.”

If theres one thing trophy bucks have in common, it`s their love of solitude.

Only seldom will a P&Y animal hang around an area where human scent is

present. In searching out these bailiwicks, look along secondary coulees or washes

feeding a creek/river bottom, away from foot traffic. During the rut in late

October or November, bucks hang out around these points creating scrape

lines.

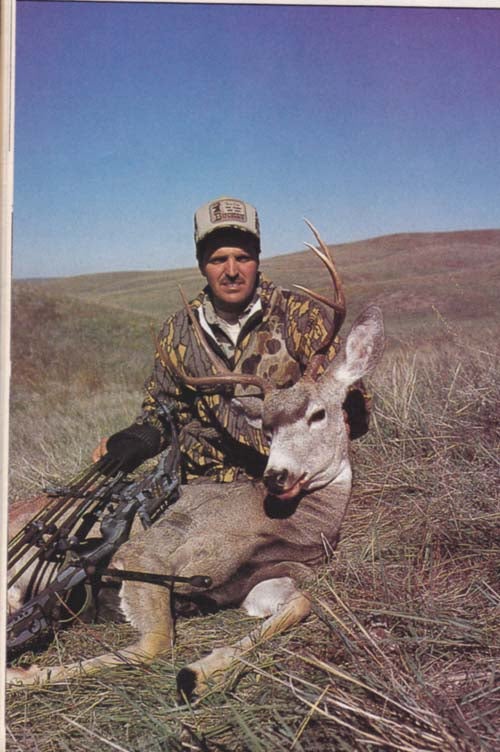

In 1987, 1 returned to Faith, South Dakota, for an either/or mulie—whitetail

hunt in the brushy creeks north of town. On the fourth day of my five—day stay, I

discovered such a hot spot. The area was a strong iifty—minute hike from the

nearest access gate. From scrape and rub activity, I guessed several bucks

were using the same staging area. That evening, I got a glance at one of the

participants. Then, on the last day, I took a chance on a forty—yard shot and tagged a

good 5×5. My ticket then was a brief grunt session using a Quaker Boy tube.

Periodically, you`ll discover a creek bottom that provides whitetails with a

natural corridor to food plots without their being seen. Usually these areas are

jungled with dense undergrowth consisting of plum thickets, waist-high grasses

or willow. With few trees to support a tree stand, the bowhunter must still—hunt

the fringes, slowly and deliberately.

With luck and perseverance, you may score.

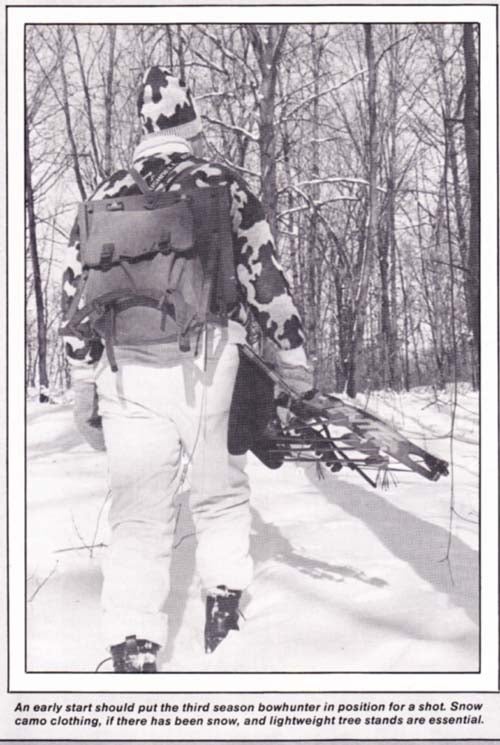

If you work the rut exclusively — November 8-30, depending on locale —

when trees and brush are bare, camo should be combinations of grays and

browns. And don`t ignore the face and hands. In many grassland states, the

ratio of success usually is measured in how well the bowhunter is camoed.

Again, flatland bucks have eyesight second to none.

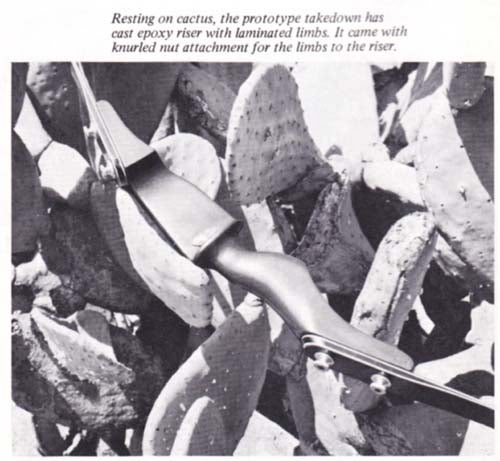

About a decade ago, overdraws hit the market with a whimper, but today

they are big business. And, if there’s a place where these devices shine, it`s in

the grasslands. Using an overdraw with cam—powered bows, a 2013 shaft

pushed by seventy pounds drops very little at fifty yards. Thus, accurate sixty-

plus—yard shots are possible. If you don’t own an overdraw, use the lightest-

spined arrow for your draw length poundage. A few grains plus or minus

make a big difference in trajectory at distances beyond thirty-five yards. By

fletching your arrows with four three-inch plastic vanes, you can stabilize

low—profile blades, even in windy conditions.

Another piece of equipment I feel grassland bowhunters shouldn’t be

without is a hand-held rangefinder. They`re light, portable and accurate. By

arriving early, you can “range” and mark a number of points and be ready

for all comers. In dim bottoms and bleak grasslands, it’s tough to estimate

distance, so a large animal usually causes shots to be short. Even though

most bucks are taken within forty yards. there are times when grassland bucks

make their own way.

During my 1988 hunt on the North Fork of the Moreau River at Usta,

South Dakota, I played the odds, placing my stand on a trail leading from a

bedding area. Much to my dismay, an “elevator” buck showed on a path

directly behind me. The rangefinder said fifty—plus yards. Within seconds, the

2013 X—7 was on its way. It was an easy mark and the buck traveled thirty

yards before piling up. If you miss an opportunity, chances are the buck will

avoid the area completely for a time.

Even with overdraws, rangefinders and cam—powered bows, the hunter

needs every advantage to get a leg up on these flag—tailed wizards. Even then,

nothing is sure until the last minute of the hunt. Last season, Wyoming expert

Leo Dube used rattling exclusively and had trouble keeping the small bucks out

of his setup. Duane Bernstein used a bleat call with some success in 1988.

My best performance came from using a combination of grunts and rattling. The

innate curiosity of the whitetail is legend and making it work is a matter of

experimenting.

For readers interested in hunting grassland bucks, the opportunities are

almost endless. Beginning in South Dakota`s Badlands near Belvidere and

continuing west through northeastern Wyoming near Hulett, whitetails roam

wide and free. To the south, central Nebraska’s Platte River region west of

Grand Island is great. Eastern Colorado`s plains south of Sterling is another prime

habitat worthy of consideration. So is northwestern Kansas, west of Hill City.

And so the story goes. <—<<<

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices